It was a picture of America that didn’t quite look like the 1950s American dream. There were cars and jukeboxes, snapshots of life on the road and in the great, booming cities. But in highlighting the daily lives of 20th-century Americans, Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank, also helped articulate an American counter-narrative of racism and inequality.

Frank, who died Monday at the age of 94, spent two years traveling across the United States, taking photographs that seemed to delve beneath the surface even if he was only showing the exterior view of a window. In 1959, 83 of his images were published in the U.S. as “The Americans,” which became a seminal collection of documentary photography and his most famous work.

Much of Frank’s images still resonate today, in both his direct style and subject matter. But if there’s one that speaks best to America in that moment, said Sarah Greenough, senior curator and head of the Department of Photographs at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., it may be “Trolley—New Orleans, 1955.”

“In the back of the trolley is this African American man, who looks out with an almost plaintive expression, questioning expression, about why the world is perhaps this way,” Greenough said, describing the image.

Greenough said that in looking at Frank’s contact sheets, they could tell he had snapped this picture “almost out of the corner of his eye” and without thinking about it, catching the moment through his “immediate intuitive release of the shutter.”

Greenough worked personally with Frank to curate an exhibit devoted to “The Americans” at its 50th anniversary in 2009. The National Gallery of Art is also home to the largest public collection of his work today. The PBS NewsHour spoke with Greenough about the lasting impact of Frank’s work.

Can you point out, in your opinion, the most important photograph in Robert Frank’s “The Americans?”

One of the most important photographs in “The Americans,” one of the most celebrated ones, is this one of the trolleys in New Orleans. It was a picture that Frank made in the fall of 1955, just a few weeks before Rosa Parks in nearby Montgomery, Alabama, had refused to give up her seat on a bus.

“Trolley—New Orleans,” (1955) by Robert Frank, from “The Americans” Photo courtesy of National Gallery of Art

As you can see, it shows a trolley, and we see in the front of the trolley, two older white people, two children in the middle of the trolley. The boy looking out, I think, with an almost quizzical expression, as if to ask the photographer and then also us, the viewer, “What is this world? What is going on?”

In the back of the trolley is this African American man, who looks out with an almost plaintive expression, questioning expression, about why the world is perhaps this way. You can see here the rigidly segregated society that existed in New Orleans at that time.

One of the really interesting facets about the picture is those who are old enough to remember segregated buses, particularly perhaps those in the South, in New Orleans, might notice that the little girl has her hand resting not actually on the back of the seat itself, but a little bit higher than the seat. And it turns out that her hand is resting on a piece of wood that indicated the “colored section” of the bus. And that piece of wood could be picked up and moved backwards if there were no more seats for white people on the bus. So, if you get on this bus at that time, and there was no seat for a white person you could pick that up move it to the next row of seats and all of the African Americans would have to get up and move one seat back on one road.

It’s a really, I think, chilling expression of racism in this country at that time.

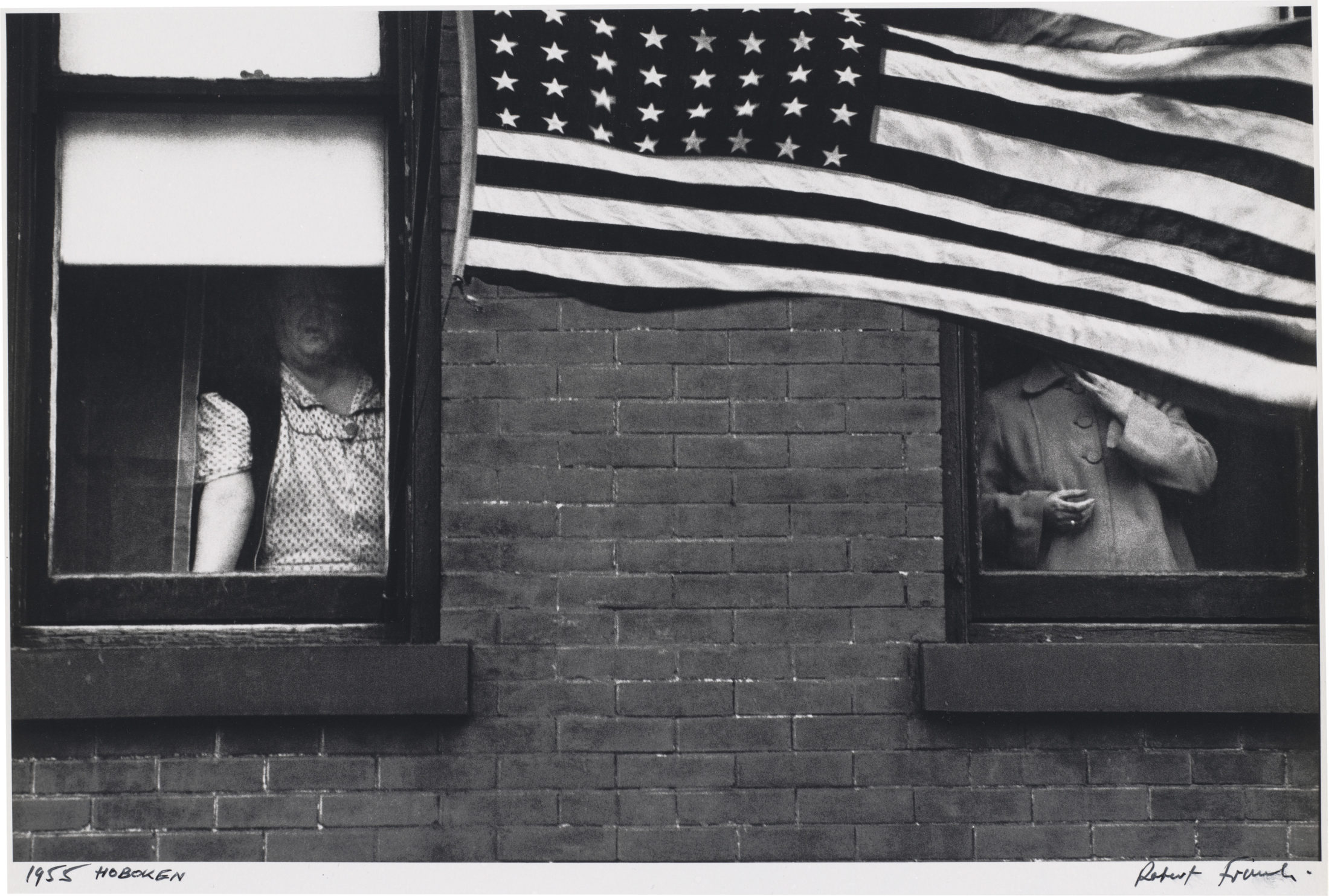

“Parade – Hoboken, New Jersey,” (1955) by Robert Frank, from “The Americans.” Photo courtesy of National Gallery of Art

What techniques in this photo, or others, show Frank’s capability as a photographer?

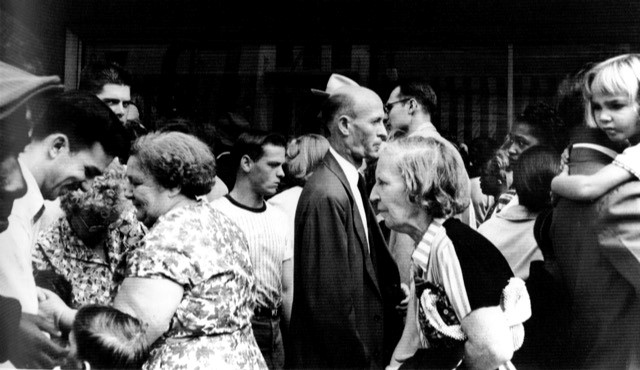

One of the wonderful things about the National Gallery’s collection is that we have all of the contact sheets that Frank made after he shot the negatives. He would place each strip of film on a piece of photographic paper and make what’s called contact or proof sheet. And if we look carefully at this we can see that Frank was on the streets in New Orleans photographing what looks like a demonstration of some kind. There are a lot of people milling around.

We can see if we look carefully that he made one picture which is also in “The Americans,” called “Canal Street,” of people just seemingly to anonymously pass each other by without acknowledging their presence.

“Canal Street – New Orleans,” (1955) by Robert Frank, from “The Americans.” Photo courtesy of National Gallery of Art

If you look through all the contact sheets, you can see that when Frank went to each city or place that he visited in the United States, he was very much in tune to try and figure out what he thought expressed the spirit or character of that place. There are pictures that he took in Miami that are of people in the hotel elevators, because Miami at that time was experiencing a great boom in construction. When you went to New Orleans, we when we looked through the contact sheets, we can see that he immediately recognized that the trolleys there in New Orleans were configured so that each of the roads were neatly framed by the windows themselves, as if the windows are putting a picture frame around each person. To a great extent, he sort of primed the pump, as it were, by noticing this feature of New Orleans, which he had seen in the days that he had been there.

Why do you think the trolley photo resonates so much today?

Because it still speaks about issues that we’re dealing with today in contemporary society, the racism that exists within America, and also because it’s such a poignant and powerful picture.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eRp8G0e9OhnGannpp6s7vBnqmtZZanrq%2B3jKmfqKyfYsGprdNmpKKfmKl6o7HSrWScmaCpwrOxjJqknqqZmK4%3D